Philippe Druillet Master Study in Pen and Ink

There are two ways I like to study the great masters of pen and ink.

Both approaches are valuable for growing your skills and knowledge as an artist.

I’ll demonstrate how you can apply these methods as we review the works of French comic artist Philippe Druillet.

//DISCLOSURE: I earn a small commission when you use my affiliate links to make a purchase. Read the Terms for more information.

Method No.1 – Start with the End in Mind

Start from an objective.

What skill are you aiming to develop?

What knowledge are you missing?

If you have selected a masterpiece, how will studying this master’s work bring you closer to your end goal?

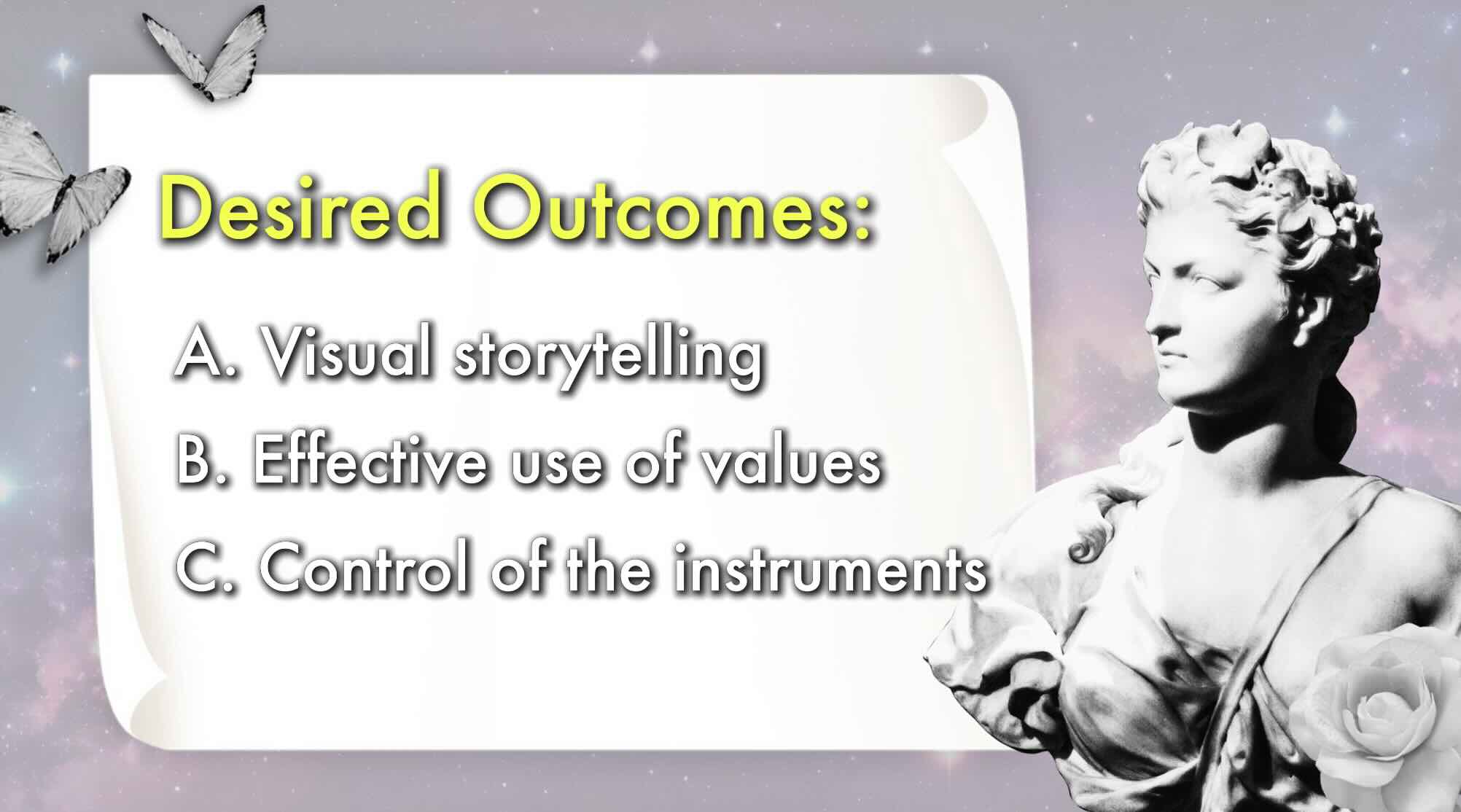

Specific Outcomes

As someone who approaches learning through an analytical mind, I focus on specific outcomes for each study session.

When there’s a purpose to an exercise, it saves you from getting overwhelmed and keeps you on track with what’s most relevant for your growth.

Having specific goals helps narrow your lens of observation.

When you know what to pay attention to in a master’s work, you’ll have a stronger focus. It turns practicing into small, digestible chunks. Then the learning gaps seem less daunting.

The benefit of this approach is that it gives you full control of the pace of your learning.

This is how I build assurance that I’m working on the right things for consistent progress.

For example:

Three of my objectives for the next six months are related to composition. Such as:

- Visual storytelling

- Effective use of values

- Control of the instruments – I want to improve with using brushes.

These three outcomes become my lens of observation.

I would therefore look at the works of masters in search of those answers. I would research masters who are renowned for these particular fundamentals.

If you turn your objectives into questions, they then become your study guide.

So, first question…

A. How does master Druillet achieve visual storytelling?

It doesn’t have to be rocket science, sometimes the obvious is the answer.

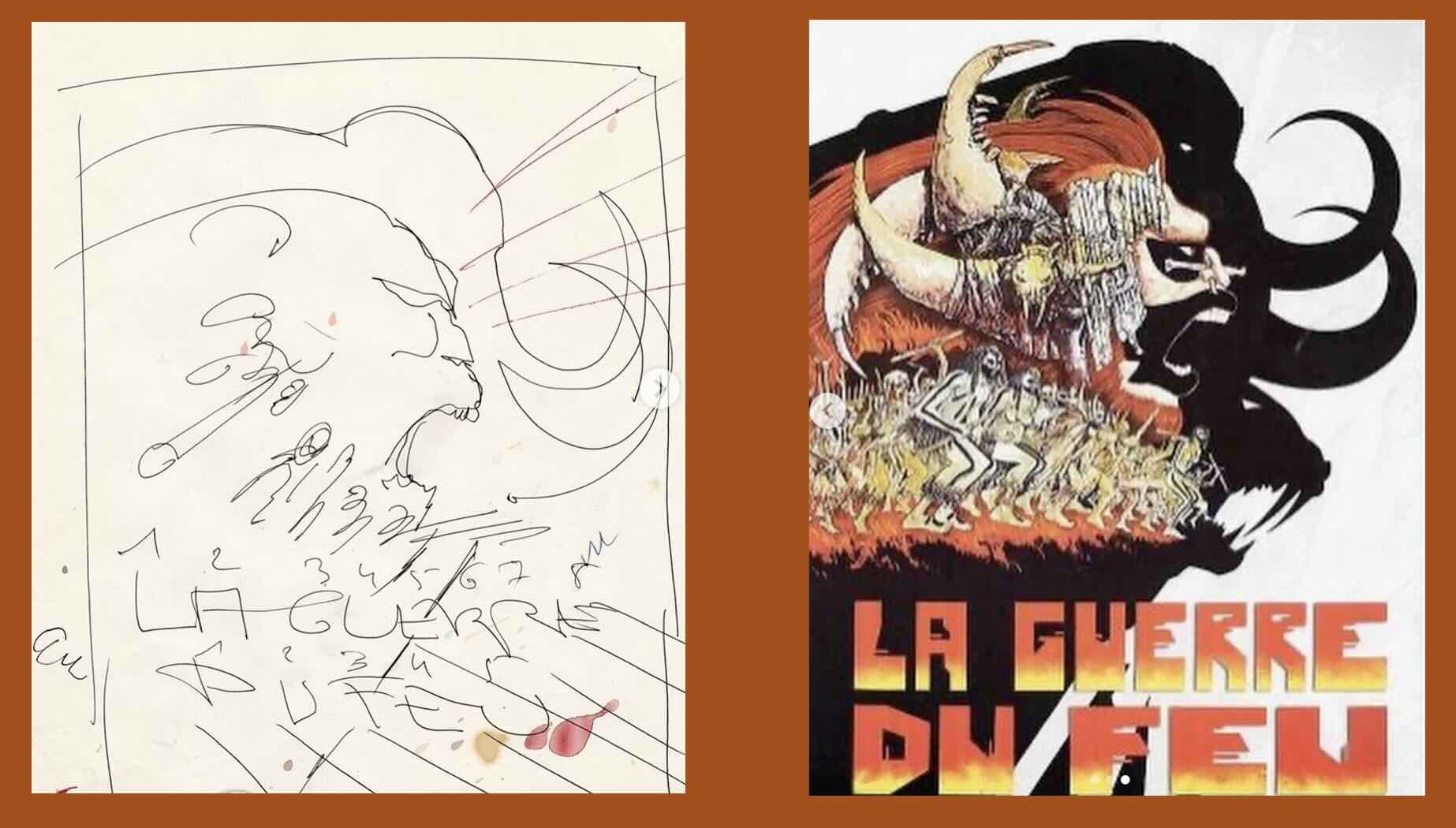

And in this case, Druillet is renowned for otherworldly visual design.

Even if you’ve never read the novels he’s illustrating, each scene invites curiosity. Like there’s a mystery to resolve.

So, his answer to visual story telling is great design.

His worlds and characters are innovative, rendered in a cohesive style.

A clue is how he assembled the elements and values on the picture plane.

You’ll observe that master Druillet pays close attention to balance, symmetry, and space.

From this observation, it’s easy to deduce that this master plans his compositions.

He probably does a lot of research and rough sketching of concepts.

You can thereafter verify your assumption by researching after your study, to confirm your observations.

That’s why I’ll often begin a master study just by looking at the art before I research about the artist or their process. I like to prove my theories afterwards.

This is how you gain knowledge.

If you made the correct observations, then you’re assured that you’re working on the right things for consistent progress.

Question number two…

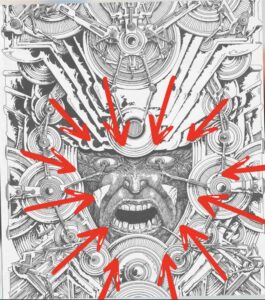

B. How does Druillet use values in his compositions?

This is where I’d pay attention to the master’s distinct rendering style.

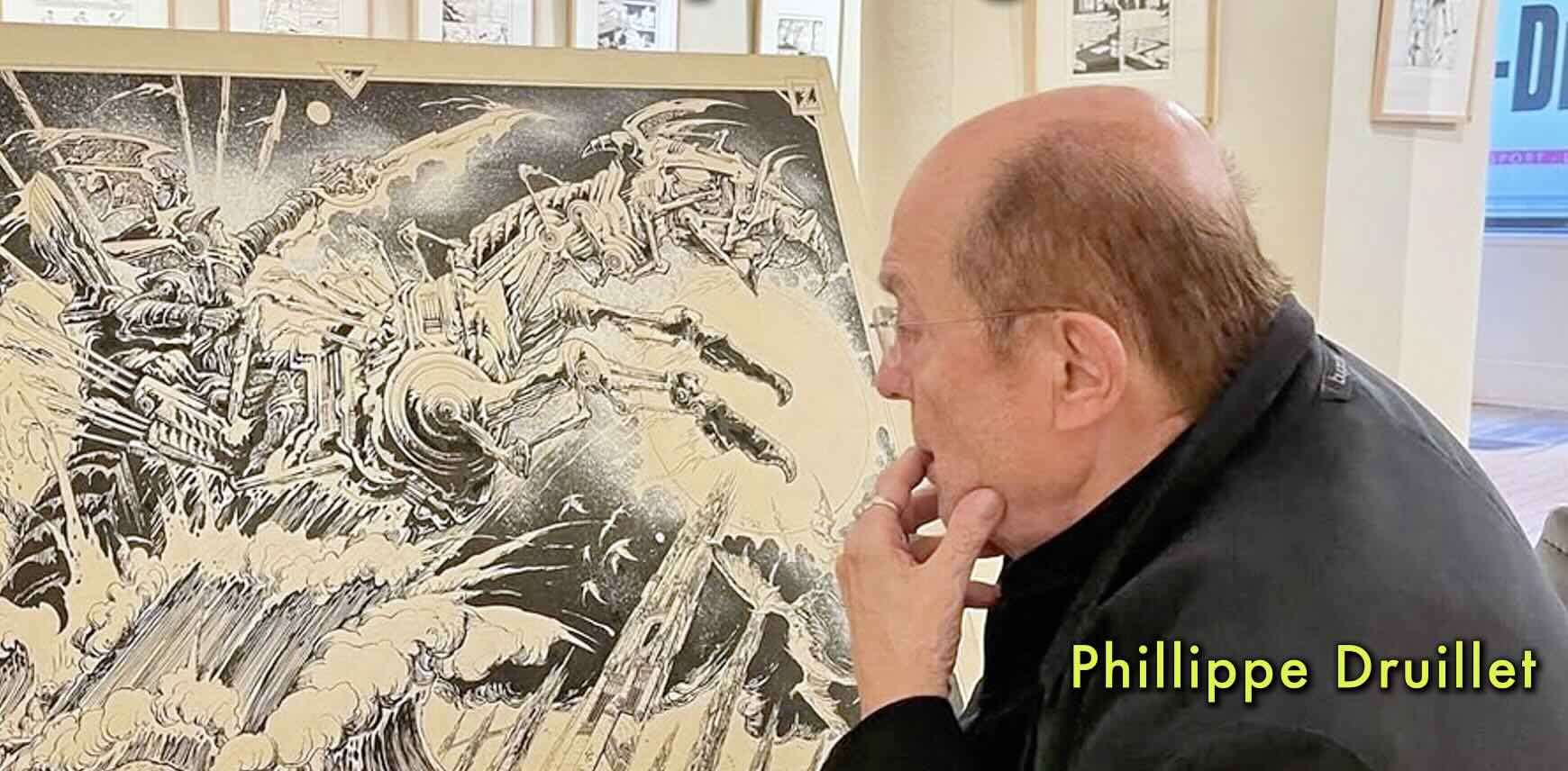

In the example below, he’s framed the main subject with high contrast values, black against white, with sparse rendering. The outlines and marks are executed with complete precision.

The contrast seems even more absolute because of how he rendered the main subject against the background – in an organic freestyle hatching texture, using the full spectrum of values.

In the second example, he did the opposite. The main subject has sparse rendering, and the background is fully rendered with values.

Question number 3…

C. How does Druillet control his instruments?

Observation alone can’t provide those insights.

I would therefore render samples of the master’s work to experience a sense of his technique.

Now we’re developing skills.

This is also where you fight the urge to render in your own style because the point is to gather information from the master.

We’re more interested in how the master made decisions and what’s informative about those choices.

This is when copying is okay. The intention of copying in this context is to learn how the master achieved the effects we seek to emulate.

It’s this step of the process where I learn the most. That’s because it’s super easy to compare my study against the master’s work.

It’s a means of feedback.

I can assess for myself:

- Are my lines shaky and timid, or controlled and fluid?

- Do my values match the master’s?

- Did I place the contrasts in the right spots?

It’s like having the answer sheet of a test, where you can readily gauge what needs more practice and what is on track with your learning objectives.

Is it:

- Shaky lines?

- Mismatched values?

- Ineffective contrast?

Those factors could be related to needing more practice with my inking tools, but could also be related to:

- My drawing or observation skills.

- Maybe I simply don’t have enough experience to recreate what I see.

In any case, now I have more relevant information. And as a result, I can adjust my learning plan to keep growing consistently as an artist.

📖 For more tips on goal setting for artists, read:

So, we looked at how to do a master study by starting with the end in mind.

This works well if you’re clear on your learning objectives and you favour a step-by-step analytic approach, as I do.

But not every artist learns this way.

Method No.2 – Start with Exploration

Myself I create from a place of logic. Art is about problem-solving.

My inspiration comes from an external source. Many of you create with an inspiration that comes from within.

Maybe for you, art is a sensation of expression. You’d be more motivated by exploration and learn best as you discover.

To you, a plan or goal might even stifle your creativity.

If that’s the case, then method number two might be more suited to your learning preference.

Which is to start with exploration.

In the previous method, specific goals helped narrow the frame of observation.

In the exploration method, it’s more of a feeling, so we want a wider lens.

You therefore pay attention to what that feeling tells you. Essentially, notice what you notice.

For this Phillipe Druillet study, rather than look at a bunch of his illustrations, you would start by copying a single piece.

You can:

- trace the entire image;

- render mini sections, or;

- practice just the textures.

Start with whatever is most enjoyable or the opposite: what seems most intimidating.

What’s important is to reflect on the why.

The 5-WHY’s Model

To drill down, I use the 5-why’s model.

This leads you to uncover the key takeaway from the study session.

1 – Why was this enjoyable, or if you did the opposite – why was this intimidating?

Once you’ve figured that out, dig deeper.

Let’s say you answered, “It was intimidating because Druillet’s compositions are so busy and I didn’t know where to start”.

A follow-up question to that could be:

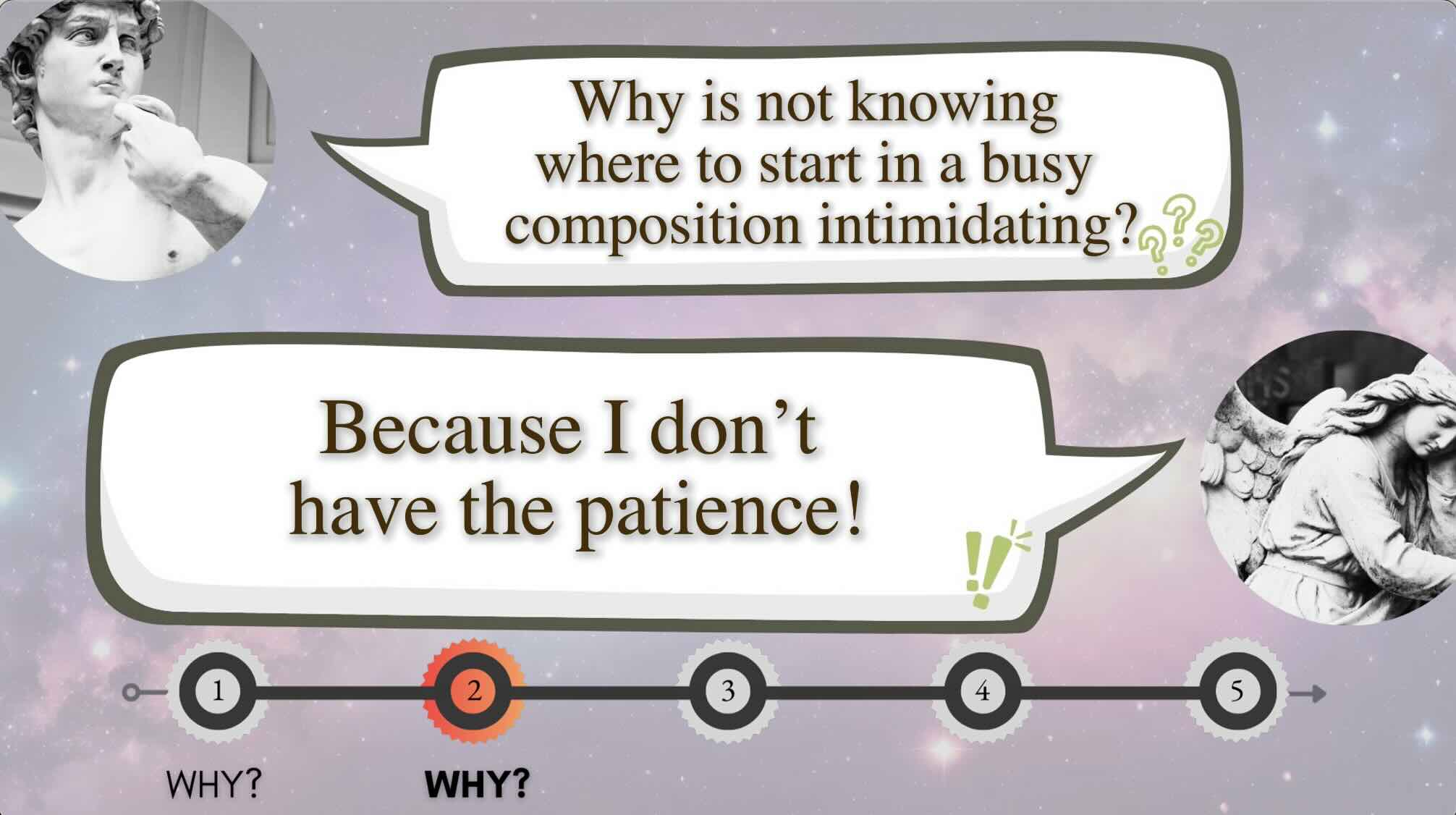

2 – Why was not knowing where to start in a busy composition intimidating?

A common answer to this might be:

“Because I don’t have the patience.”

A follow-up question could be:

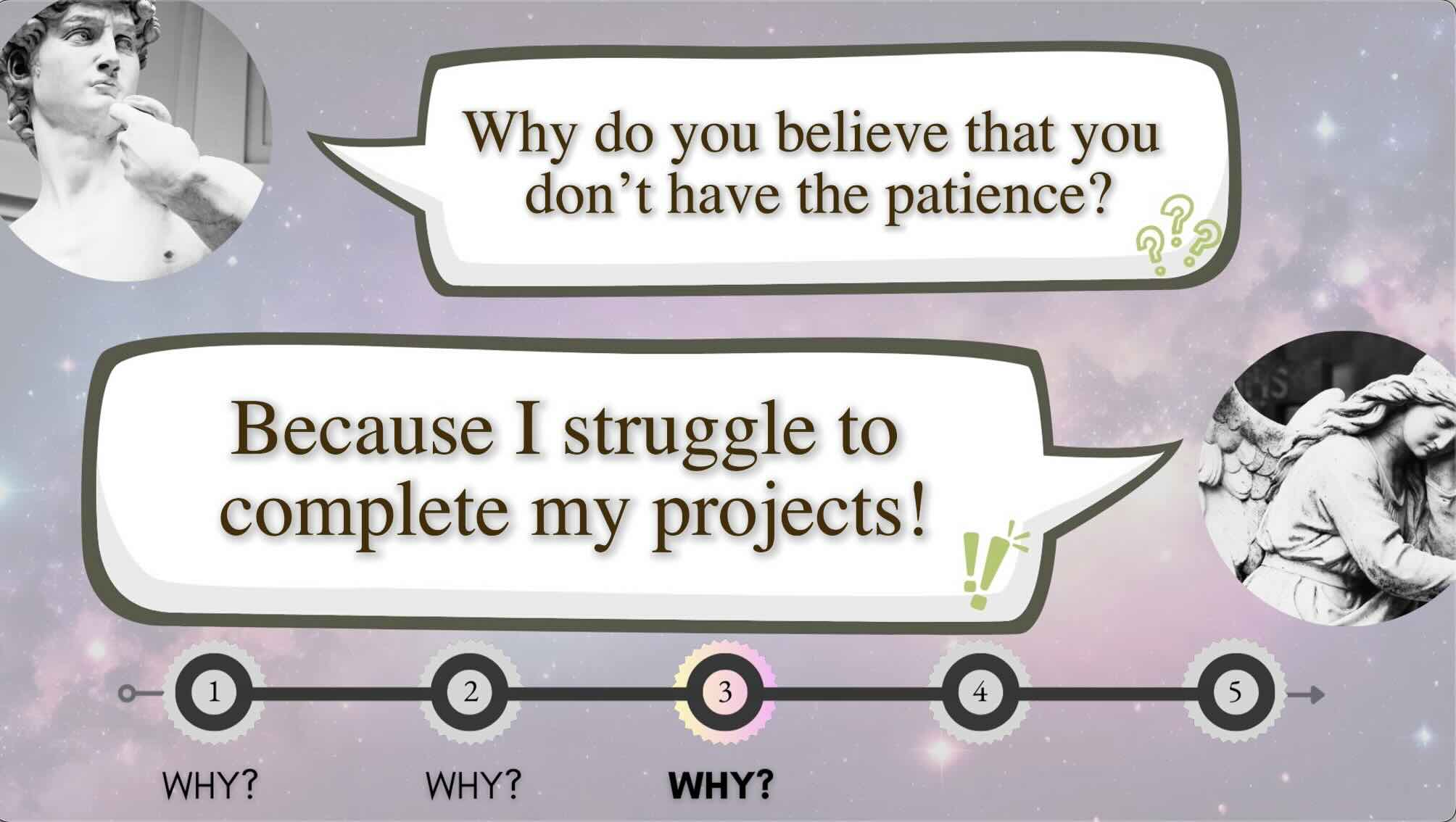

3 – Why do you believe that you don’t have the patience?

The answer to this might be:

“Because I rarely finish my projects, I can sketch but have trouble completing a piece.”

Then a follow-up question to this could be:

4 – Why do you have trouble completing a piece?

You might be tempted to answer “I don’t know” but a mentor would challenge it is because you have no compelling reasons to complete the piece.

When you have a vision, a plan, goals, and a purpose for completing a piece, you find patience.

It’s more motivating to stay consistent when you have a reason to keep at it.

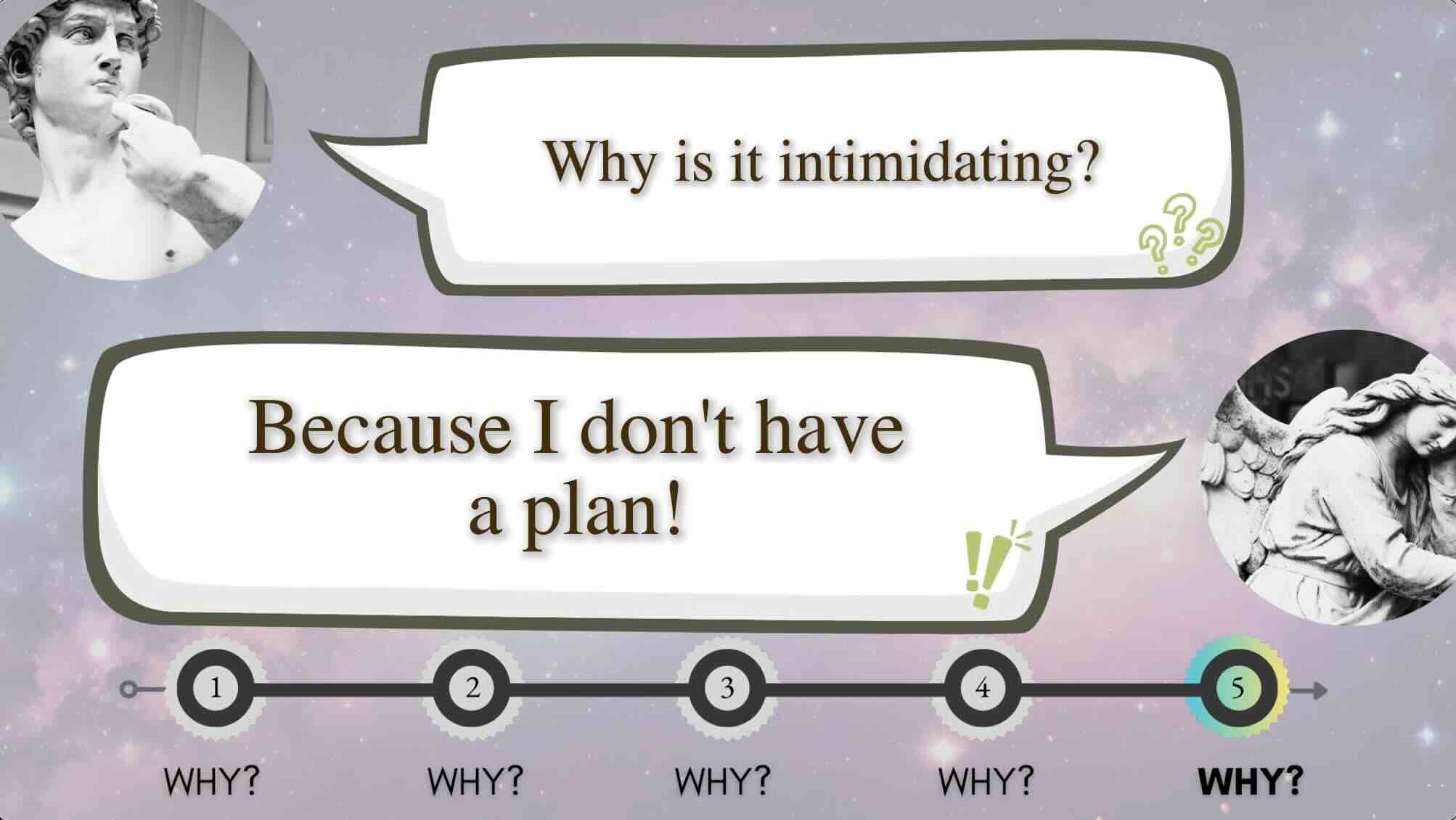

If you want to dig deeper, you can ask a 5th follow-up question, like;

5 – Why is sketching easier than finishing a piece?

You get an idea of how this model works.

At the end of the 5-Why’s exercise, you’ll have insights into what could become compelling reasons for your next study session.

Or at the very least, you now have more information about what gets in your way of growth and what could enhance your learning.

What’s great about this method is that, through exploration, you discover objectives to pursue.

Instead of starting with a plan, you’ve uncovered one that is most relevant to you.

Depending on your learning preference, one method may be more appealing.

However, whenever you want to stretch your comfort zone, you can try the other or combine them.

📖 For more on your learning preferences, check out Get The Results You Want.

The next step is to apply your learnings.

Apply Your Learnings

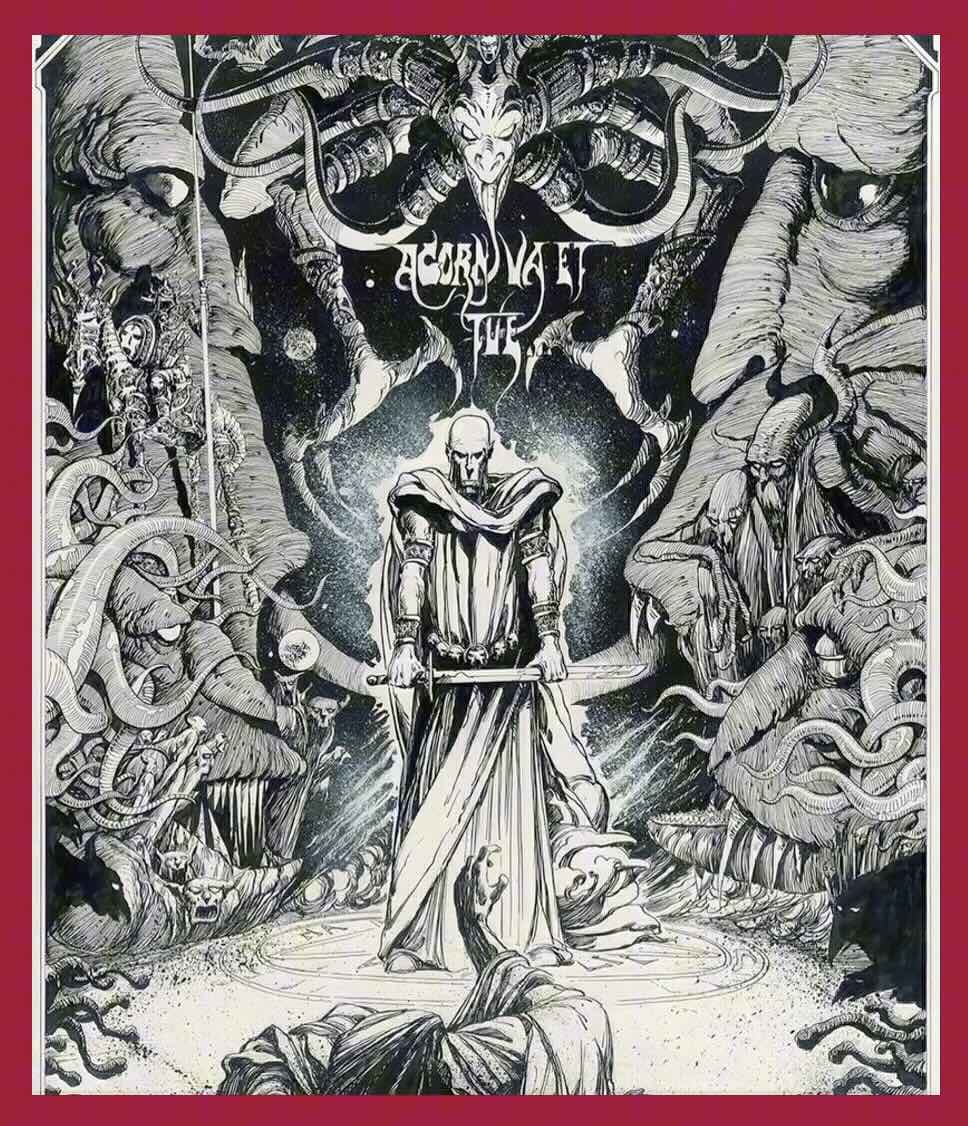

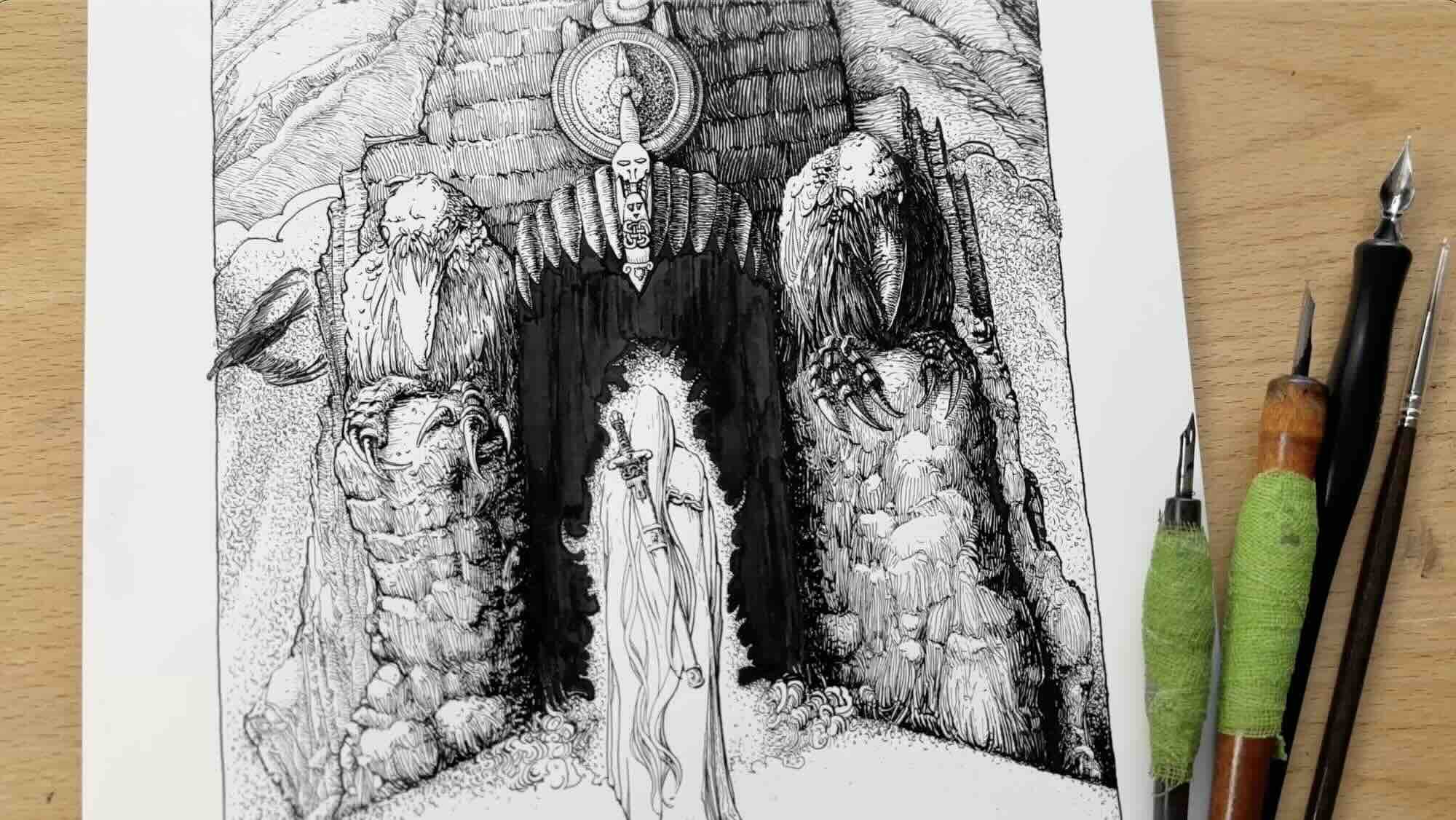

After doing sample studies of master Druillet’s works, and going through my study questions, I immediately designed a composition.

This is when you can test out the techniques learned from your studies, either rendered in your own style or emulating the master’s style.

In this final piece I focussed on Druillet’s:

- Visual storytelling

- Effective use of values.

As for control of the instruments, I used a brush for the solid areas as the master did in his pieces.

The genre of the piece and stroke techniques are inspired by the master’s collective works.

TIMING: It took about three days to complete my original piece. One day for pencils and planning. Two days for the ink application.

I hope that you enjoyed these two approaches on how to get the most from your master studies.

If you did, let me know in the comments which of the two approaches most resonated with you.

Resources

More Druillet by @RichardFriendartist

📗 Books ↓↓↓

✒️Tools ↓↓↓